I never knew my grandfather Joe. He’d been in the army since his teens as a member of the Royal Horse Artillery’s ‘L’ Battery. He was born in 1890 in a tiny house opposite the gasworks in London’s Pimlico (long before it was fashionable), and he was 24 when war broke out. He was a soldier and a horseman, just like his father before him.

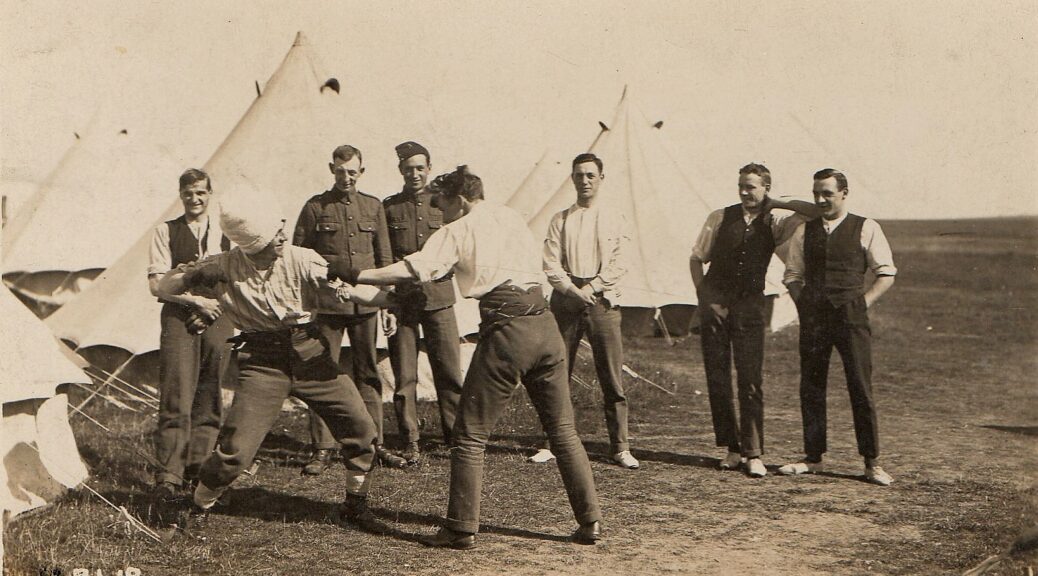

Before the war, there’d always been time for a bit of levity for Gunner Joseph Eyles (right, boxing) as he and his friends underwent cavalry training on Salisbury Plain.

But back at Aldershot, Joe’s life was beginning to intersect with that of a very different kind of career soldier.

His Royal Highness Prince Prajadhipok of Siam, or to give him his full name, Phra Bat Somdet Phra Poramintharamaha Prajadhipok Phra Pok Klao Chao Yu Hua, was one of King Chulalongkorn’s younger sons. Considered unlikely to succeed to the throne, he’d been prepared instead for a military career. After attending Eton and Woolwich Military Academy, he was commissioned to the Royal Horse Artillery and stationed at Aldershot, where from January until early August 1914, Joe was his batman, or, in other words, his valet and chauffeur. Joe was a lifelong socialist, a staunch trade unionist in later years, and I’ve often wondered how this brush with wealth and royalty made him feel.

When war broke out, and Joe’s regiment shipped out to France as part of the British Expeditionary Force, Prince Prajadhipok unwillingly returned to Siam. After the early deaths of his brothers, he was destined to become King after all, and was eventually crowned King Rama VII in 1926.

As things turned out, he was to be Siam’s last absolute monarch. Despite his efforts to bring peace to a troubled nation and an ill-advised European tour which included a visit to Nazi Germany, he was forced to abdicate in 1935 as Siam became a constitutional monarchy and began the transition to modern Thailand.

Meanwhile, back in France, Joe had been keeping a war diary. It detailed his experiences of the Battle of Mons in 1914, the subsequent retreat and ‘L’ Battery’s famous action at Néry on September 1st in which all the officers, a quarter of the men and most of the battery’s horses were killed. Here’s how he recorded it:

At 4.30am a hazy mist enveloped the ground, and we were watching guns and troops on a far crest quite unconcernedly thinking they were French when all of a sudden we received a terrific shelling and as we were unprepared, some of us shaving, partially undressed, etc, horses with their nosebags on and saddles off, it was a sight I shall never forget. Everyone not lucky to get under cover were blown to atoms. Our losses were heavy, horses suffering most and out of 240 we only had 18 sound. Our officers 3 were killed, the other 2 seriously wounded, the loss amongst other ranks was also great. “L” R.H.A. with Cavalry and infantry came to aid, silencing and capturing 10 German guns and taking 600 odd prisoners. Luckily after a while I managed to secure a riderless Uhlan’s horse, vault into the saddle and effect my escape, and at nightfall by which time I had joined up with Brigade HQs.

‘L’ Battery were celebrated as heroes and given a couple of month’s leave back in England to recuperate. But, after returning to the war, Joe lost his elder brother Fred, who died in Flanders in 1916. A reconstituted ‘L’ Battery went out to Gallipoli and then back to the Western Front, and at some point before the end of the war, Joe experienced the gas attack which left him with long-term respiratory disease. In this he was not alone; although only 3% of those gassed died immediately, hundreds of thousands of ex-soldiers continued to suffer chronic ill-health for many years after the war.

Despite his health problems, Joe was able to use his reference from the Siamese Legation detailing his service to Prince Prajadhipok to help him get work as a driver after the war. He’d married his sweetheart, Dolly, in February 1918 and they had one daughter, my mother Josie, in 1924.

The family survived the London Blitz, somewhat narrowly – Joe had a lucky escape during an air raid while making deliveries, when a shell cap came through the roof of his van and landed just behind his seat. The incident made the very papers he was delivering!

Sadly, however, Joe didn’t survive long into the period of peace and rebuilding that followed World War II. My mother remembered the protracted coughing fits which kept him awake – and probably the rest of the family (all of whom were sharing the tiny, terraced house in London’s Elephant and Castle) – at night. Joe died of chronic bronchitis and asthma on 29th January 1951, when he was 60 years old – just over seven years before I was born.

To mark the centenary of World War I, the Imperial War Museum invited descendants of those who were involved in the conflict to contribute our ancestors’ stories, with photos and other media. These were then checked, curated and stored to make a unique remembrance project – a crowdsourced digital record of ordinary people’s experiences of the conflict called ‘Lives Of The First World War’.

As for the exiled Prajadhipok – he settled in Compton House, a mansion in Surrey’s Virginia Water, where he died of a heart attack in 1941. He’s remembered in his home country with a museum in Bangkok documenting his life and his place in history.

by Clare O’Brien

More information:

- Joe Eyles’s ‘‘Lives Of The First World War’’

- A full account of the action at Néry

- A history of the Royal Horse Artillery’s ‘L’ Battery

- Information on Prince Prajadhipok/King Rama VII

- King Projadhipok museum

Throughout November we’re inviting our beloved Autumn Voices members to submit any short piece of writing about War & Remembrance. It should be no longer than 300 words and can take any form you wish. At the end of November, we’ll pick our favourite and the author will receive a copy of Codebreaking Sisters by Patricia and Jean Owtram. The publisher, Mirror Books has very kindly given us a copy to offer as a prize.

Entries are closed.

Very evocative… thank you for sharing your grandfather’s story.

Thank you Clare for such a wonderfully and movingly written account of your grandfathers war experience . So sad that he had to suffer and eventually lose his life through chronic respiratory disease .

We all owe him our gratitude .